Art and music

of the community, for the community

View the photographs-

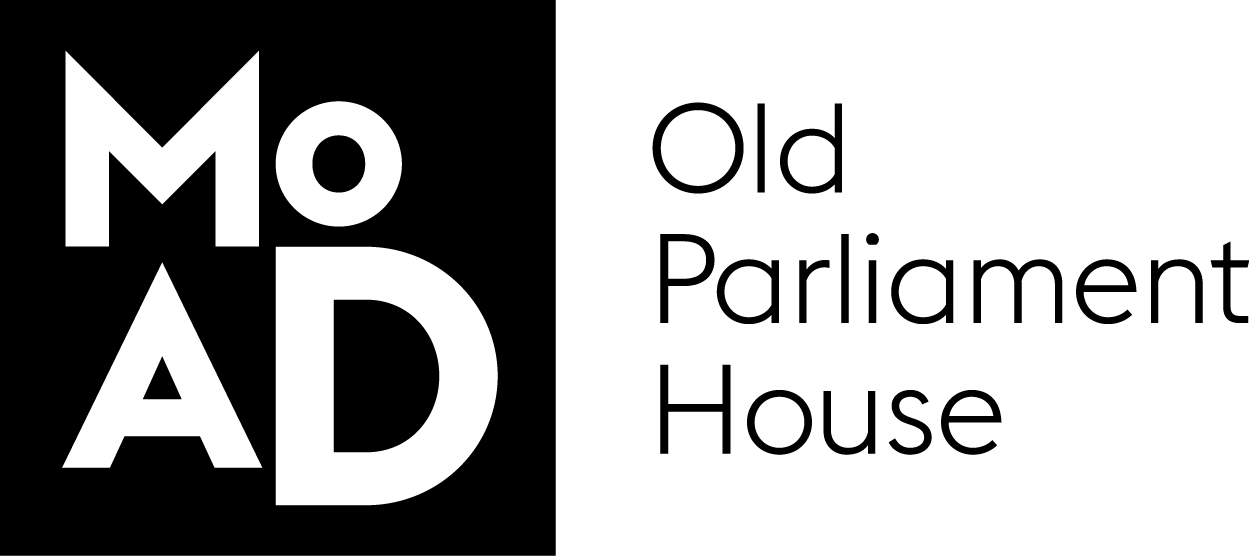

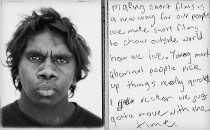

Morika Biljabu comments on art and culture

Morika Biljabu comments on art and culture

-

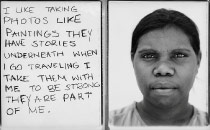

Wokka Taylor paints his country

Wokka Taylor paints his country

-

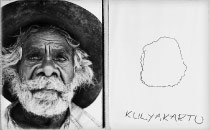

Yunkurra Billy Atkins paints a pangarra

Yunkurra Billy Atkins paints a pangarra

-

Curtis Taylor comments on art and culture

Curtis Taylor comments on art and culture

-

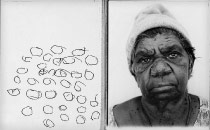

Kumpaya Girgiba paints her country

Kumpaya Girgiba paints her country

-

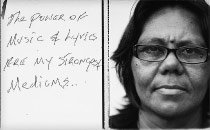

Lorrae Coffin comments on music and culture

Lorrae Coffin comments on music and culture

-

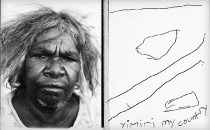

Yuwali Nixon paints her country

Yuwali Nixon paints her country

-

Fran Haintz comments on Indigenous affairs

Fran Haintz comments on Indigenous affairs

‘Painting makes me happy. Martu are painting stories for Martu and for whitefellas to have a look at. We want people to see that Martu culture is kunyjunyu (good).’

Yunkurra Billy Atkins, Martumili artist

From traditional painting, dancing and singing, to the modern art forms of theatre, literature, film-making and photography, Indigenous artists have been at the forefront of keeping their stories, culture and history alive.

Read moreThe several bark petitions submitted to the Australian parliament since 1963 show just how interconnected art, land and politics are in Indigenous culture. The typewritten texts were bordered with drawings. They were, in fact, a form of land deed or map, of equal importance to the words. Community leaders were exposing sacred knowledge, thereby asserting ownership of country. It was a politically astute move, being an attempt to find common ground between two systems of law. Much Indigenous art still draws on traditional knowledge of the land and sometimes is submitted as evidence in court cases.

Indigenous artists have not only promoted their culture within Australia, but have taken it to an international audience, where it is widely acclaimed, highly valued and much-collected.

Yikartu Bumba and granddaughter Sophra Marney painting at Parnngurr, 2009

Parnngurr, Western Australia

Photo Tobias TitzA 2007 Senate report estimated the Indigenous art industry was worth up to A$300 million. ‘Aborigines do not view their art as a commodity,’ the report emphasised, ‘but more a communal asset to be shared.’ The cooperative structure of the art centres empowers the whole community, ensuring that the much-needed income is widely distributed. Art is the basis for self-sufficiency in several remote communities.

The report also noted that ‘In the past six years the Papunya Tula artists have funded a dialysis unit at the Kintore community and raised A$900,000 for the construction of a swimming pool, which helps reduce eye diseases amongst children who swim in the chlorinated water.’

Many of the artists at the Martumili Arts Centre in the Western Desert were late to ‘come in’, living traditional lives until the mid-1960s. It is one of three art centres in the Pilbara region, more recently established than those in Central Australia and the Top End. The Yulparija Artists of Bidyadanga have been painting since the early 2000s; the Roebourne Art Group was established in 2005; and Martumili Artists started in 2007 to support the growing arts industry in the Pilbara. In these art centres people from all generations mix–the old teaching the young, remembering country and sharing stories.

Martumili artists most often paint their country with details vital for survival such as food sources and water. Landmarks, such as the rabbit-proof fence, are shown as alien white lines. Kumpaya Girgiba has drawn yinta (‘living waters’), jurnu (ephemeral soaks) and rock wells north and east of Well 33 on the Canning Stock Route.

In 2007 BHP Billiton Iron Ore announced that it would contribute seed finance of $400,000 to Martumili Artists over three years. A highly successful exhibition at William Mora Gallery, Melbourne, launched the artists on to the art scene in 2006–Martu-La Wakarnu Kuwarri Wiyaju (Martu Painting Together First Time).

For Martumili artists this was their first foray into the commercial art world, but theirs is a society that has been painting, singing and dancing for thousands of years. Indigenous artefacts were once dismissed as a primitive expression of a dying race, but it is now evident that the culture survives as a vibrant, contemporary force.