‘We said, ‘No. We’re not going back to the station no more. No more. We’re not going back’

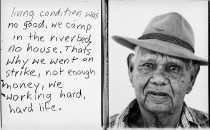

Nyamal elder, Peter Kangkushot Coppin, was one of the key figures during Australia’s longest strike

On 1 May 1946, nearly 800 Indigenous pastoral workers throughout the Pilbara defied the Aborigines Act 1905 (WA) and walked off in protest over lack of personal freedom, poor pay (often only rations) and sub-standard living conditions.

Read moreUnder the Act, pastoralists were granted permits to employ Indigenous workers, who were then not legally able to leave the station, nor travel below the 20th parallel, without a permit. Vast fortunes were built on this virtually captive, largely unpaid workforce.

A six-week meeting of 200 Indigenous Lawmen in 1942 had reached consensus about striking, but action was deferred until after the Second World War. Then the Pilbara Strike was meticulously organised by Nyamal man Clancy McKenna, Nyangumarta man Dooley Bin Bin, Nyamal man Peter Kangkushot Coppin and Don McLeod, who police reports called a ‘white stirrer’.

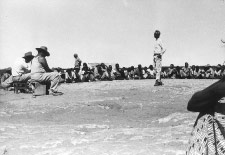

Stockmen, gardeners and house servants walked off pastoral stations throughout the Pilbara.

Ernie Mitchell with Peter Coppin listening to arguments for and against ‘the split’ of the company Pindan Pty Ltd, 1959.

Believing Indigenous people incapable of such independent action, officials accused McLeod of being the ringleader, but he wrote ‘I didn’t co-ordinate the strike. The Lawmen had a good tight grip on the whole business.’ McKenna and others were periodically jailed for ‘enticing natives from their lawful service.’

Despite constant harassment the strikers sustained themselves yandying (a method of surface mining) for tin, and trading skins and pearl shells. After three years their determination and tenacity were rewarded with improvements to pay and conditions for Indigenous people. But many never returned to work for the ‘whitefella’.

Port Hedland resident Judy Charlene who was a young girl during the strike, recalled ‘We went everywhere looking for gold and tin and trying to make our own money. We had to buy our own clothes and tucker; it was the first time we were independent.’

The dream of economic independence was eventually realised. The successful cottage industries they established, especially the profitable mining concerns, built self-reliance and confidence. The Group, as they became known, registered the first Indigenous-owned company in Western Australia in 1951, and went on to own several pastoral stations.